Modernism

Defining Modernism

Modernism is a cultural movement of the late

nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that rejected past ideals as failed,

and seeks new ideals to replace them.

Modernists thought that the art, writing and philosophies of the past

were artificial, false and unsound.

It was hoped that a new approach based on honest and fearless

reassessment of human nature and society would produce a better civilization. The movement began before World War I,

but the war greatly intensified the perception that that past ideas had failed,

and new ones were desperately needed.

Modernist thinkers believed foremost that

European culture had a superficial understanding of reality. After the war,

grand theories and ideals which promised to explain everything and lead to a

greater future were utterly discredited. Even idealism itself seemed to

be misguided. The truth seemed more complicated and erratic.

A good example of this sort of thinking is

the novel you read, All Quiet on the

Western Front. This novel was published in 1929, and offers a modernist

view of the war. It was a huge European best-seller in the 1930s.

One German commentator wrote that "the effect of the book springs in fact

from the terrible disillusionment of the German people with the state in which

they find themselves, and the reader tends to feel that his book has located

the source of all our difficulties." An American critic wrote that

it encapsulated the whole modern impulse--an amalgamation of prayer and desperation,

dream and chaos, wish and desolation. The optimism of the past seemed to

inappropriate and inadequate.

In this new

mood of pessimism, Christianity suffered terrible decline in Europe, along with

other cultural and social traditions. One might expect a religious revival in

times of difficulty, but the rejection of past tradition contributed to a steep

decline of religious observance in Europe after the war. Christianity

before the war was bound up in spirit of the day. Protestants especially

embraced a more optimistic, humanistic outlook. They celebrated the value

of individual faith and also devotion to nation and the empire. All these

things were discredited after the war. In the face of war and economic

depression, the individual seemed insignificant. Hope seemed out of

place; empires crumbled, and the nation-state proved weak and

untrustworthy. It seemed to many Europeans that there was no benevolent

God, or that at least the institutional churches had nothing to say to them.

Modernists were

not all about negativity, however.

They were eager to find new paths forward. That is why early twentieth

century modernism was a time of great innovation. We will focus our discussion on the artistic side of the

modernist movement, in which you can literally see and hear the ideals and

aspirations of that time.

Abstract Art

Modernism in the fine arts can be crudely

defined as abstraction in art, functionalism in architecture, and atonality in

music. In each case, the hope was to discover a new and more reliable

truth.

Abstraction was the move away from imitating

reality in visual arts. Instead of reproducing a scene or likeness of a person,

the abstract artist worked with shapes, lines and colors to create an image

intended to provoke thought rather than simple recognition. One form of

abstraction was called "surrealism," an art form popular in the

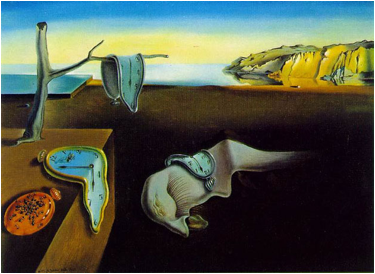

1930s. A famous example of

surrealism is Spanish painter, Salvador Dali's Persistence of Memory

Salvador

Dali, Persistence of Memory (1931)

Salvador

Dali, Persistence of Memory (1931)

As you can see, surrealism is a form in which

familiar objects are distorted and placed in unfamiliar arrangements. This

painting has a dreamlike quality to it, and suggests something about time and

perceptions of our subconscious mind. What sort of "truth" does it

try to tell?

Functionalist Architecture

Modern architecture has a good deal in common

with modern art. It too is

abstract in nature, using basic shapes, lines and colors to build a

vocabulary of design. The German architect Walter Gropius is

considered one of the most important innovators, teaching his new ideas at his

Bauhaus School of Design in Germany. He designed the building for the school,

which became a model of the new style.

Walter Gropius, Bauhaus Building (1925)

Walter Gropius, Bauhaus Building (1925)

Gropius believed that better design would

improve human lives, and help society progress. The key, in his mind, was to

build buildings that conformed to human needs (functionalism) rather than being

merely traditional, decorative or impressive. One way to serve needs is cheapness

and convenience. Square buildings

with flat roofs built of steel and glass were cheaper to build and add onto,

and the openness of the building brought more natural light into the interior. People in the building would have more

usable space, more natural light, and also the good views of the natural

outdoors. Gropius believed the such a building was both more functional

and more beautiful, because it was it was elegantly simple, and blended with

nature. If all people had good

places to work and live, he reasoned, the quality of life would increase for

all.

Atonal Music

Modernist composers hope to reinvent music

too. The equivalent of abstraction

and functionalism in music was atonality.

This means an escape from the traditional scales and harmonic systems of

classical music, and exploring a larger range of sounds. A famous innovator in music was the

Austrian composer Arnold Schoenberg, who developed the "twelve-tone"

or "serial" system. The traditional major or minor scales are made of

up 7 notes. But there are actually

12 pitches in every scale. Why not

use all 12? Choosing the 8 notes

seems arbitrary, but using all twelve is more natural, he reasoned, because our

ears can naturally distinguish twelve tones. He set about to create new music on this basis.

Watch the following YouTube clip so you can

hear it for yourself.

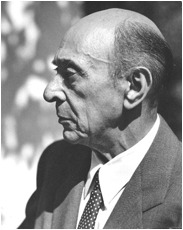

Arnold Schoenberg

Arnold Schoenberg