The Imperialist Venture

Cecil Rhodes in South Africa

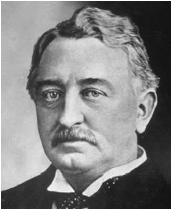

Cecil Rhodes

was the son of a parson in England. As a young man of 17 in 1870, he left

home with an older brother to farm newly claimed land in the Natal colony in

Southern Africa. At that age he soon found himself in charge of a farm

with 30 black laborers. A year later he joined the rush to stake a claim

in the newly discovered diamond fields near the town of Kimberley, in the Cape

Colony.

Cecil Rhodes

was the son of a parson in England. As a young man of 17 in 1870, he left

home with an older brother to farm newly claimed land in the Natal colony in

Southern Africa. At that age he soon found himself in charge of a farm

with 30 black laborers. A year later he joined the rush to stake a claim

in the newly discovered diamond fields near the town of Kimberley, in the Cape

Colony.

Kimberley in 1871 was the wild west of the British

Empire. It was a boom town of 20,000 whose mines produced about $2

million a day worth of diamonds in current dollars. Whites established

claims only a few yards across and hired black laborers--who were locked in

segregated compounds-- to dig down hundreds of feet. Rhodes and his

brother earned the equivalent about $5000 a month on their three claims.

Men made money fast and lost it fast gambling, drinking and speculating.

Stories abounded of fortunes gained and lost--of claims being sold as

worthless, only to have the new owner dig out huge diamonds a few feet further

underground.  .

.

In 1876 the limit on the number of claims one could hold was

lifted, and Rhodes was one who bet the Diamonds would not give out.

Rhodes wheeled and deeled with financial backers in London, and claim holders

in Kimberley to get a controlling stake in one of the smaller mines, called De

Beers. By 1888, he cut a deal with some of the other major owners to buy

them out, and gain sole control of the entire Kimberley diamond field under his

company, De Beers Mining Company. Rhodes had control of most of the

world's diamond supply, and he was also one of the richest men in the world.

(De Beers still controls the world's diamond supply today).

In 1889, Rhodes used his fabulous wealth and power to found

another company, the British South Africa Company, which was to explore and

settle in the name of the British Empire unclaimed areas of southern

Africa. He created two new colonies, Upper and Lower Rhodesia (named

after himself, of course) which today are the countries of Zambia and

Zimbabwe. In From 1890 to 1896, he served as the Prime Minister of the

Cape Colony, the main British colony in southern Africa.

Rhodes's career is a celebrated and illustrative tale of

European enthusiasm for imperial expansion in Asia and Africa in the late 19th

century. There was money to made and fabulous opportunities for power for

those lucky enough and stout enough to manage it. There was fame and

glory to be one both for individuals and nations that established themselves in

the last remaining "uncivilized" portions of the globe. There

were also terrible wars to be fought, as I will mention later.

The New Imperialism

The terms "new imperialism" and "classical

imperialism" have been used to describe the period roughly from 1880 to

1914, when European nations scrambled and competed with each other to claim new

colonies throughout Africa and Asia. The scramble began when Britain

moved in troops to occupy Egypt in 1882. In spite of his general

opposition to such military expansion, Prime Minister Gladstone felt compelled

to occupy Egypt (supposedly temporarily) to prevent the sultan who was

pro-British from being overthrown by anti-European factions. Britain

stood to lose a great deal. The Egyptian government owed a lot of money

to British and French investors. But the greatest fear was that an

anti-European government might close down the new, French-built Suez Canal that

linked Europe and Asia, and particularly Britain with its prize colony,

India. And so Britain expanded its empire in Egypt to preserve its

existing empire in India. The discovery of diamonds in South Africa in

1867, and then huge gold deposits in the late 1870s suddenly made southern

Africa more valuable too, and the British moved to establish their control in

the region

The Colony Race

As Britain advanced its hold in Egypt and southern Africa,

France moved to establish its control of northern and western Africa, starting

with its long-established colony in Algeria, just across the Mediterranean from

France. French advocates of imperialism were motivated in the first place

by the humiliation of their defeat in the Franco-Prussian War in 1871.

The establishment of a vast empire in Africa would make France great again, and

able to stand up to both the Germans and British. They rushed to beat the

British in staking claims along the West African coast and in central Africa

south of Egypt. To compete with Britain and Holland's vast holdings in

Asia, France moved in the 1880s to establish colonies in southeast Asia,

colonies that later became Vietnam and Cambodia.

Germany lagged far behind Britain and France in the race for

colonies. Germany was just born as united country, and had very little in

the way of a merchant marine or navy. But by the middle of the 1880s,

Bismarck realized that Germany could not afford to be left out entirely, and

moved to make strategic claims around Africa to break up the monopoly of

Britain or France. The United States, too, joined the race for colonies.

We provoked and won a war with Spain in Cuba the Philippines, and took those

colonies, along with Hawaii and Puerto Rico for ourselves.

Two

failures

Russia also attempted to expand its empire in period,

southwards into central Asia and eastwards in Siberia. Unlike France,

Germany and Britain, they met with defeat. The British prevented Russia

from expanding into Afghanistan or Balkan Europe. In 1905, Russia and

Japan fought over pacific islands off Siberia, and Russia suffered a

humiliating defeat. Italy attempted to occupy Ethiopia, but also suffered

a humiliating defeat. Both countries carried for many years after a chip

on their shoulders for their national failures.

The Growth of the Imperialist Ideals

The expansion of European empires was not merely a

geo-strategic concern of national governments, it was also an important

cultural development for European nations. It seemed a perfect

confirmation of what we now call Social Darwinism, the idea that some races or

nations were more advanced in evolutionary terms, and therefore superior and

more fit to rule. Imperialism was the continuing progress of humanity

that Darwin promised in his theory of evolution.

This enthusiasm for evolutionary progress was often fused

with a rather romantic sense moral duty in the British mind. John Ruskin, a

famous essayist, told an Oxford University audience in 1871 that:

There

is a destiny before us, the highest ever set before a nation to be accepted or

refused. We are still undegenerate in race; a race mingled of the best

northern blood. We are not yet dissolute in temper, but still have the

firmness to govern and the grace to obey. . . . Make your country .

. .for all the world a source of light, centre for peace; a mistress of

learning and the Arts, faithful guardian of time-tried principles. . .

this is what England must do or perish; she must found colonies as fast and as

far as she is able, formed of her most energetic and worthiest men; seizing

every piece of fruitful waste ground she can set her feet on, and there

teaching those of her colonists that their chief virtue is fidelity to their

country.

Cecil Rhodes echoed this sentiment a few years later in his

diary:

I

contend that we are the finest race in the world and the more of the world we inhabit

the better it is for the human race . . . It is our duty to seize every

opportunity of acquiring more territory and we should deep this one idea

steadily before our eyes; that more territory simply means more of the

Anglo-Saxon race, more of the best, the most human, most honorable race the

world possesses. . .

Another very important source of enthusiasm for

empire-building was the missionary movement. The churches of Britain,

Germany and the US--especially the evangelicals--along with the Catholic

Church, greatly expanded their efforts to civilize (Westernize) and convert the

populations of Africa and Asia. They were often the first

explorers, and commonly established the first trading posts in new

territories. As they established footholds in new communities, they would

ask their governments to establish troops and administrators to help

"civilize" the native peoples, and also protect them from their

rivals, or from predatory traders or other Europeans eager to stake their own

claims.

Historians of women at this time have recently paid more

attention to the reason why many women, including feminists, supported

Imperialism. Women often had greater opportunities in the empire as

doctors, teachers or missionaries or politicians than at home, and came to see

empires as an important calling to advance the cause of women as well as

Western Civilization around the world.

The Poet of Imperialism

Take the time to read through Rudyard Kipling's poem, the

"White Man's Burden" (p. 870) Kipling was an immensely talented

English poet and fiction writer who grew up and lived most of his life in

India. Consider both the tone and message of the poem. Kipling had

a particular view of the moral value of British imperial rule. What is

the moral value? Why is the empire good?

The Dangers of Imperialism

While imperialism appeared to be very good thing to many

Europeans, there was great costs to be paid. First was that even though

European nations avoid outright warfare in Africa or Asia, there was still a

great expense of blood and treasure to hold colonies that could not in economic

terms pay for themselves. The mostly costly war occurred in South Africa,

when Britain fought Dutch-descended settler for control of the gold fields

around Johannesburg. (The Boer War, 1899-1902) Because the Boers were

well-armed and tenacious European settlers, the war dragged on for three years,

and 10s of thousands were killed, including civilians. This went far in

dampening enthusiasm for empire, and created some anti-imperialist sentiment

also.

The idea of European domination through conquest stood in

contradiction to the professed European values of democracy and freedom..

This contradiction was increasingly troubling to both native peoples and the

Europeans themselves, who had to admit the contradiction, and were forced to

admit that eventually Asians and Africans deserved freedom and

independence. Imperialists argued that it would take a long time, however,

before that could happen. The native peoples, naturally, disagreed, and

Western-educated natives soon founded independence movements in the early

twentieth-century.

The most deadly cost of imperial expansion was the

heightened competition and rivalry between European nations. The search

to gain ground in geo-political and economic terms in comparison with European

competitors was an increasing concern. Germany and Russia in particular

were profoundly concerned that they were falling behind the race for world

power, and must act to reverse it. German fear of France, Britain and

Russia was confirmed when these three nations formed an alliance to contain

German influence and expansion. Russian and German interests were in

direct competition in Eastern Europe, and their refusal to compromise

diplomatically was a major cause of World War I. Imperialism and national

competition came with a very high price tag indeed.